The aging process is an intricate and multifaceted phenomenon, with the human brain undergoing a series of changes over time. Yet, despite the undeniable importance of understanding the biological mechanisms underpinning brain aging, there remains a conspicuous scientific gap in our knowledge.

In a study published recently in Ageing Research Reviews (“Healthy brain aging and delayed dementia in Texas rural elderly”), a team of researchers from the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) School of Medicine sought to address this gap by delving into the intricate interplay of biological, psychosocial and environmental factors that may influence healthy cognitive aging.

The team, led by P. Hemachandra Reddy, Ph.D., included Tanisha Basu, M.S., Malcolm Brownell, Ph.D., Hallie Morton, Erika Orlov and Ujala Sehar, Ph.D., from the TTUHSC Department of Internal Medicine; John Culberson, M.D., from the TTUHSC Department of Family Medicine; Hafiz Khan, Ph.D., from the TTUHSC Julia Jones Matthews School of Population and Public Health; and Keya Malhotra, M.D., from the TTUHSC Department of Internal Medicine and the Grace Clinic at Covenant Health System in Lubbock.

To initiate the study, the Reddy team assembled a cohort of 25 cognitively healthy individuals and five individuals diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Their ages ranged from 60-90 years.

The study utilized a comprehensive approach that combined anthropometric measurements (quantitative body measurements to estimate a person’s nutritional status), blood biomarker testing, surveys and structural brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The paper reveals the baseline characteristics of the two groups and highlights significant correlations and distinctions that provide critical insights into the complexities of healthy brain aging.

To begin the investigation, the study team recorded and compared various baseline characteristics of both groups, including age, body mass index (BMI), body weight, height, body fat percentage, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and blood biomarkers. The CCI is an index of 19 conditions used to predict the risk of death within the first year of hospitalization for patients with specific comorbidities.

“At this initial stage, individuals displaying healthy cognitive aging and those diagnosed with MCI/AD exhibited comparable measurements in anthropometrics and blood biomarkers,” Brownell explained. “These findings suggest that, from a purely physiological standpoint, there were no discernible differences between the two groups at baseline.”

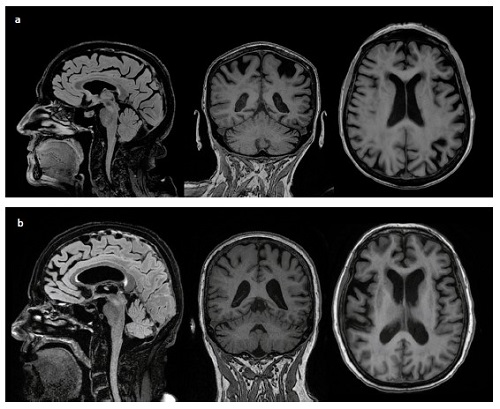

One of the study’s cornerstones involved structural brain MRI scans, a critical tool for examining the integrity of the aging brain. Culberson said the results of the structural brain MRI scans uncovered striking differences between the two groups. For example, the cognitively healthy group exhibited fewer signs of brain volume loss. The observed reductions were predominantly age-related, suggesting a more resilient aging process in this cohort.

a) From left to right: Saggital, coronal, and axial planes of MRI images of an 87 Y/O person with Dementia, showing decreased matter volume and signs of white matter disease. b) from left to right: Saggital, coronal and axial planes of MRI images of an 80 Y/O female cognitively healthy person, with a MoCA score of 27/30, showing age-related cerebral volume loss.

In contrast, the individuals with MCI/AD displayed MRI scans that indicated the presence of gray and white matter disease coupled with a notable loss of cerebral volume. Basu said these structural alterations align with the cognitive deficits and characteristic of MCI and AD. The study also identified other conditions related to these individuals such as small ischemic vessels and white matter hyperintensity.

The brain scans also were correlated with Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores and age. The MoCA is a screening tool used to assess mild cognitive dysfunction traits such as attention span and concentration, executive functions (e.g., planning, self-control and ability to focus), memory, language, visuospatial skills (e.g., spatial ability and motor skills coordination), conceptual thinking, calculations and orientation.

Within the healthy population, those between the ages of 60–75 years had near-perfect to perfect scores (30/30) on the MoCA and presented with no brain volume loss. Conversely, the older participants had lower scores that were closer to the passing cut-off point (26/30) and presented with age-related brain volume loss. These findings may inform future research efforts to create interventions that may prolong healthy brain aging and delay the progression of MCI to AD.

The team also identified a significant correlation between age and MoCA scores within the healthy aging group, an indication that as individuals grew older, their cognitive performance tended to decline, albeit at varying rates.

Additionally, the study identified several key trends that potentially point to important associations between cognitive tests, brain scans, blood biomarkers and other factors. For example, the study noted that individuals who engaged in one or more aspects of a healthy lifestyle – fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity and adequate sleep — tended to have higher MoCA scores. Individuals with cognitive decline, regardless of age, also reported poor sleep, lacked physical activity and presented with a higher incidence of comorbidities.

The findings of this study and the work of other scientists from across the nation will be detailed Oct. 25-27 at the second Healthy Aging and Dementia Research Symposium hosted by TTUHSC.